We had crossed over the Panamá Canal a few times, gawking at the cranes in the port area and the line of ships beyond, waiting their turn to cross from the Pacific to the Caribbean. During a siesta, we watched a PBS documentary on the Panamá Canal, part of the American Experience series, and found it educational, entertaining, and fucking awe inspiring. The U.S. created Panama just to build the canal, then had to solve enormous problems involving manpower, civil engineering, mechanical engineering, medicine, and domestic politics to get the job done. Even if you don’t plan on going to Panamá, it’s worth a watch.

New Year’s Day we headed to the Miraflores Visitors Center to check out their museum and the impressive view of the locks that separate the Pacific from the rest of the canal. Just as we arrived, a cruise ship made its way into the lock. We watched as the ship was guided along with a combination of tugboats and rail cars.

What appeared to be a building and some industrial equipment not far away slowly rose out of the other lock, revealing itself to be a cargo ship on its way to the Caribbean.

The welcome center has its own documentary, in both English and Spanish, though it doesn’t go into the level of detail as the American Experience episode and assumes you already know some of the country’s history. A portion of the museum is dedicated to the flora and fauna of the area, but the best part by far is a simulator of sorts, a room that puts you in the captain’s seat as a ship is guided through the locks. If the show had followed the full length of the canal – an 8-12 hour run – I might have sat through the entire thing.

The welcome center has its own documentary, in both English and Spanish, though it doesn’t go into the level of detail as the American Experience episode and assumes you already know some of the country’s history. A portion of the museum is dedicated to the flora and fauna of the area, but the best part by far is a simulator of sorts, a room that puts you in the captain’s seat as a ship is guided through the locks. If the show had followed the full length of the canal – an 8-12 hour run – I might have sat through the entire thing.

Since the U.S. handed over control of the canal, Panamá has jacked up the price of passage, using the money to give incentives to businesses in the capital. The increased expense for shipping companies has inspired China to back the construction of a new canal through Nicaragua, a plan that is generating a bit of controversy. Meanwhile, Panamá is building new locks to handle wider ships. This project has already generated cost overruns and, unlike the current locks, will have to recycle the water used in them to avoid draining the lake that serves the current system, so there are additional engineering problems to tackle.

We cruised up a stretch of road along the canal, spotting a few boats we’d seen in the locks making their way across the continental divide. Below is the Culebra Cut, one of the more challenging portions of the canal’s construction. Apparently, they have recently widened this section, making it a less dramatic view but decreasing the dangers from rock slides.

A few days later, we traveled further north to see the Caribbean side of Panamá. As previously mentioned, Panamanians seem to detest road signs. It’s rare to spot one, and even more rare to find one that is accurate, and almost mythical to spot one that is accurate and placed far enough in advance for it to be of any value. To make matters worse, there are a couple of toll roads that each require different pre-paid cards, so a wrong turn can end up costing you time and money.

I steered us into the wrong lane at one of the toll plazas. When I realized what I’d done, I hurriedly backed up. It was a slow, holiday weekend so there was no oncoming traffic. A policeman on foot spotted me and rushed over to direct me to the proper booth. He asked for my driver’s license but I discovered I’d left it at the hotel. He had me pull over and, after a lot of broken Spanish/English conversation, asked for money. I forked over $20 to be allowed to continue the journey. Sure, it’s corruption, but in the States I would’ve paid more for the same offense and had to deal with the court system.

We crossed over the Chagres, a river that used to flood violently every year, washing away the French efforts to dig a sea-level canal. The same river was used by Henry Morgan and company to paddle partway across the isthmus on their famous raid of Panamá City. Now, the river has been dammed to form the largest man-made lake on earth, which is part of the canal route. The same dam provides power for the canal operations. For a river of such importance, its appearance was comparatively placid.

When we got off the highway, we often ended up behind former school buses from the States turned into local mass transit. These busses are privately owned and compete with each other for riders. Some of them have been decorated to the point where we had to wonder if the driver can even see.

We headed along the Caribbean coast to Portobelo, once the largest town in the New World. Silver and gold from South America would make its way up both coasts to the town. Mule trains from Panamá City would make their way across the isthmus to meet ships in the port here. As the galleons were loaded to take their spoils to Spain, the town would host thousands for a months-long fair, during which time a rather alarming percentage of people would die from various diseases. The town is built in a mangrove swamp and lacked clean water. The town was sacked repeatedly, including a raid by Henry Morgan and associates in 1668. As the Spanish began losing control of their colonies abroad, the town of Portobelo became less and less important. Now it’s an almost forgotten village with a few ruined forts and a handful of faded Spanish Colonial buildings. The town and waterfront display a depressing amount of trash, particularly when contrasted to the beautiful setting. Here’s a 360-degree view of the harbor from Fort San Lorenzo (Note: zoom in.)

The sea oozes into the lower levels of the fort at high tide. Vultures and seagulls perch along the walls, eyeing the trash washing along the stream behind the fort. According to Wikipedia, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee placed Portobelo and Fort San Lorenzo on the List of World Heritage in Danger in July 2012, citing environmental factors, lack of maintenance, and uncontrollable urban developments. (These urban developments are difficult to spot, but it may only be that there is little oversight to what might be done.)

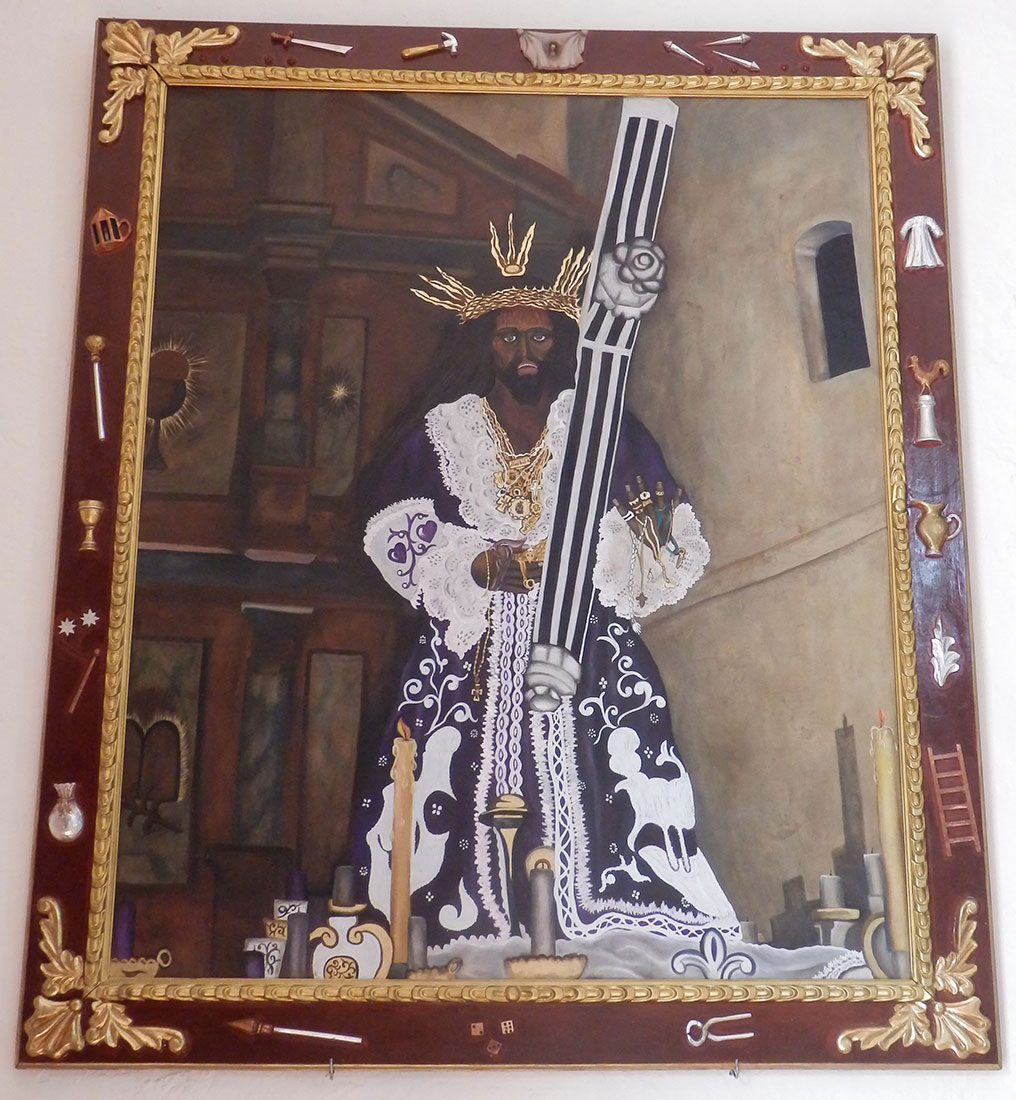

Portobelo still holds a festival every year, but these days it is in celebration of Black Jesus – no, not the TV show. The church has an interesting, blinged-out Jesus sculpture with skin tones that match many people of the area, the descendants of escaped slaves. The statue has a confusing backstory, but it’s worth checking out. The church itself is plain compared to others, but the locals take Black Jesus very seriously, changing his robes a couple of times a year and storing previously used robes in the museum in the custom’s house nearby. Unfortunately, the glare on the glass protecting Jesus prevented me from getting a decent photo, but there is a painting of the statue as well.

Portobelo still holds a festival every year, but these days it is in celebration of Black Jesus – no, not the TV show. The church has an interesting, blinged-out Jesus sculpture with skin tones that match many people of the area, the descendants of escaped slaves. The statue has a confusing backstory, but it’s worth checking out. The church itself is plain compared to others, but the locals take Black Jesus very seriously, changing his robes a couple of times a year and storing previously used robes in the museum in the custom’s house nearby. Unfortunately, the glare on the glass protecting Jesus prevented me from getting a decent photo, but there is a painting of the statue as well.

Why Jesus needs so many gold chains and is surrounded by icons from dice to a sword, I have no idea.

The customs house is one of the few buildings dating back to the 1600’s that is still standing. It houses a museum but we weren’t in the mood (it was blazing hot and the building didn’t exactly appear to have central A/C.)

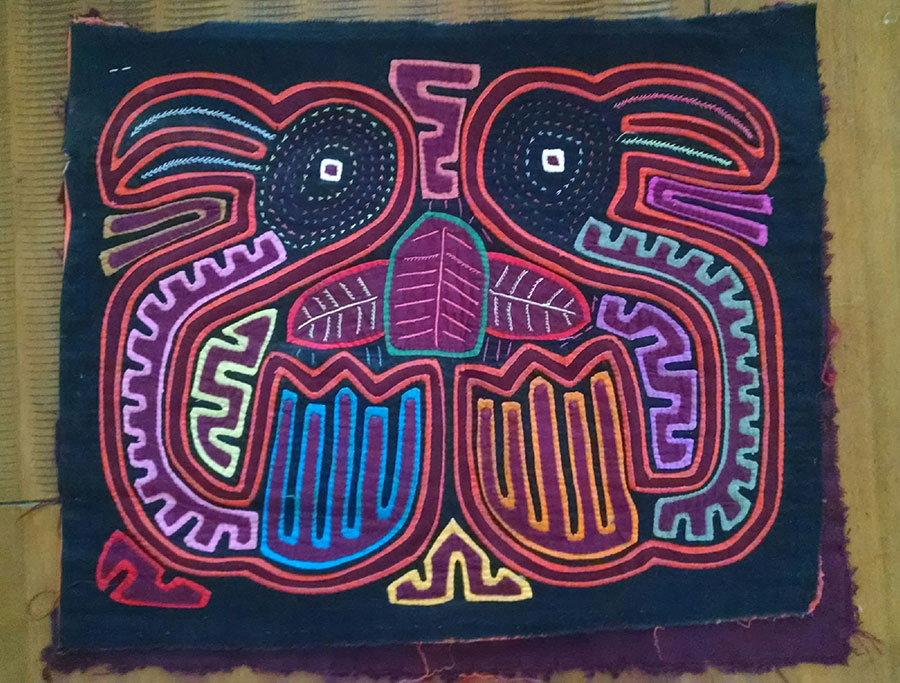

We found a few vendors selling Guna crafts and picked up a couple of hand-stitched panels, each about 18″ across and going for $10-20. I probably could’ve haggled for lower prices, but their asking prices seemed too low judging by the amount of work that into each piece.

In the local gift shop the only thing that drew my attention was this chess set featuring conquistadors battling natives.

Otherwise, there’s not much else to see in the village proper. There are jungle and snorkeling tours in the area. Combined with the historical importance, the town draws more than its fair share of backpackers. But the heat, humidity, and lack of anything else to see didn’t encourage us to linger.

Otherwise, there’s not much else to see in the village proper. There are jungle and snorkeling tours in the area. Combined with the historical importance, the town draws more than its fair share of backpackers. But the heat, humidity, and lack of anything else to see didn’t encourage us to linger.

There are a few small towns east of Portobelo where you can catch a ferry (just one of the local people with spare time, a boat, and a desire for a couple of bucks) to nearby islands occupied by native people. Unfortunately, we hadn’t arranged enough time to make the trip so we cruised on, enjoying the occasional view of the Caribbean before getting too hungry to continue on.

We had an amazing lunch of octopus in a spicy, curry coconut milk sauce, garlic shrimp, some fried starches and such at a roadside restaurant just outside Portobelo. After one last look at the Caribbean, we sped west.

The town at the north end of the Panamá Canal, Colón, was once a thriving hub of commercial activity. These days, you can’t find anything positive written about it. The Panama Railway runs along the canal and is an expensive but fairly well reviewed excursion – except for the fact that the trip ends in Colón. Judging from the reviews of the town, one might expect to be immediately attacked by a gang of vicious thugs, and then have an unscrupulous cabbie or guide rob you of your life savings for a trip to Portobelo. Even Wikepedia is cutting in its description:

During its heyday, Colón was home to dozens of nightclubs, cabarets, and movie theaters. It was known for its citizens’ civic pride, orderly appearance, and outstanding native sons and daughters. Politically instigated riots in the 1960s destroyed the city’s beautiful municipal palace and signaled the start of the city’s decline, which was further accelerated by the military dictatorships of Omar Torrijos and Manuel Noriega from 1968 to 1987.

Since the late 1960s, Colón has been in serious economic and social decline. In recent times, the unemployment rate has hovered around 40%, and the poverty rate is even higher. Drug addiction and poverty have contributed to crime and violence, which successive Panamanian governments have not addressed effectively.

Naturally, we had to see the place for ourselves. Like much of Central America, Colón is frustrating. It has so much potential. The town is packed with a mix of Deco and Spanish Colonial buildings, but the majority of them are in need of serious repair. It is built along the sea, but wealth is passing it by – literally. Tanker ships and cruise lies sit just off shore as they wait for entry into the canal. It seems all the wealth in the country is flowing into the capital and only the capital. Even some of the people of Colón appear dilapidated and sad. We saw a man wearing nothing but ragged boxer shorts, which fell off of him as he shuffled down the sidewalk in the midst of a mental health crisis – and nobody batted an eye.

Despite the rot, the streets and sidewalks were bustling, so there is life in the town yet. If there is a photographer out there looking for a gritty assignment that could be both visually captivating and bring attention to an area that is in dire need, Colón should be high on your To Do list. If there is a Panamanian politician reading this, Colón could be a wonderful town that would draw some of those tourists off the ships and out of the train station – but it is obvious the town can’t do it without some kind of help.

We wanted to get back to the capital before dark, due to the navigational challenges, so we returned to the highway and sped back across the isthmus, taking better care to mind which lanes we were in for the toll plazas.

With previous trips to El Salvador and Nicaragua, I felt like I’ve seen enough of Central America. I can easily imagine retiring somewhere in Panamá, if only my significant other could tolerate the heat. You get beautiful beaches, lush mountains, and a low cost of living, with large enough cities to provide everything you could want.

See also: